Here is a fact about me: I burn a lot of toast. It usually happens when my brain is suddenly distracted by an incoming call, text, or an attention-seeking and hungry cat bounding across the room and about to knock over a freshly-made cup of coffee on my desk, or maybe I have a lightning-bolt epiphany when I remember an appointment that I forgot to write down in my planner and realize I might be double-booked. I walk away from my toast-making task for only an instant to attend to whatever thing has distracted me and then I smell it—burnt toast.

Well, you say, try buying a new toaster that doesn’t burn the bagel so easily. True. And if I had a nickel for every time I have burnt the bagel I’d have enough money for a supremely boujee toaster. However, it would not change the fact that I have the attention span of an ill-focused goldfish.

It was not always this way, with me and burning things—and, by the way, my forgetful tendencies are not limited to the toaster. There was a time when I felt pretty good about my ability to stick with a task and even read and write comprehensively while in a crowded, noisy place with distractions abounding. This toast-burning tendency has been simmering to a boil for quite a slow while. How or why did this change in me happen? I believe it was the advent of digital screens and social media that was the trigger of what I now call my ping-pong brain.

The signs of my shortening attention span have been many. Things like not reading longer works of fiction as much as I used to, and being more amenable to texting than having lengthy conversations in person or on the phone. I could attribute these things to simply not having as much time, but when I really started noticing the decline in my ability to focus as a problem, I decided to do some Googling. Maybe it wasn’t about being too busy, or even being lazy during the times when I did have a free moment. Maybe, just maybe, it had more to do with being hopelessly distracted by the constant pull at my attention by the addictive nature and instant gratification of technology and the increasingly invasive digital world. As a woman who owes a lot of her livelihood to the wonders of technology and the internet, what could I possibly do about it?

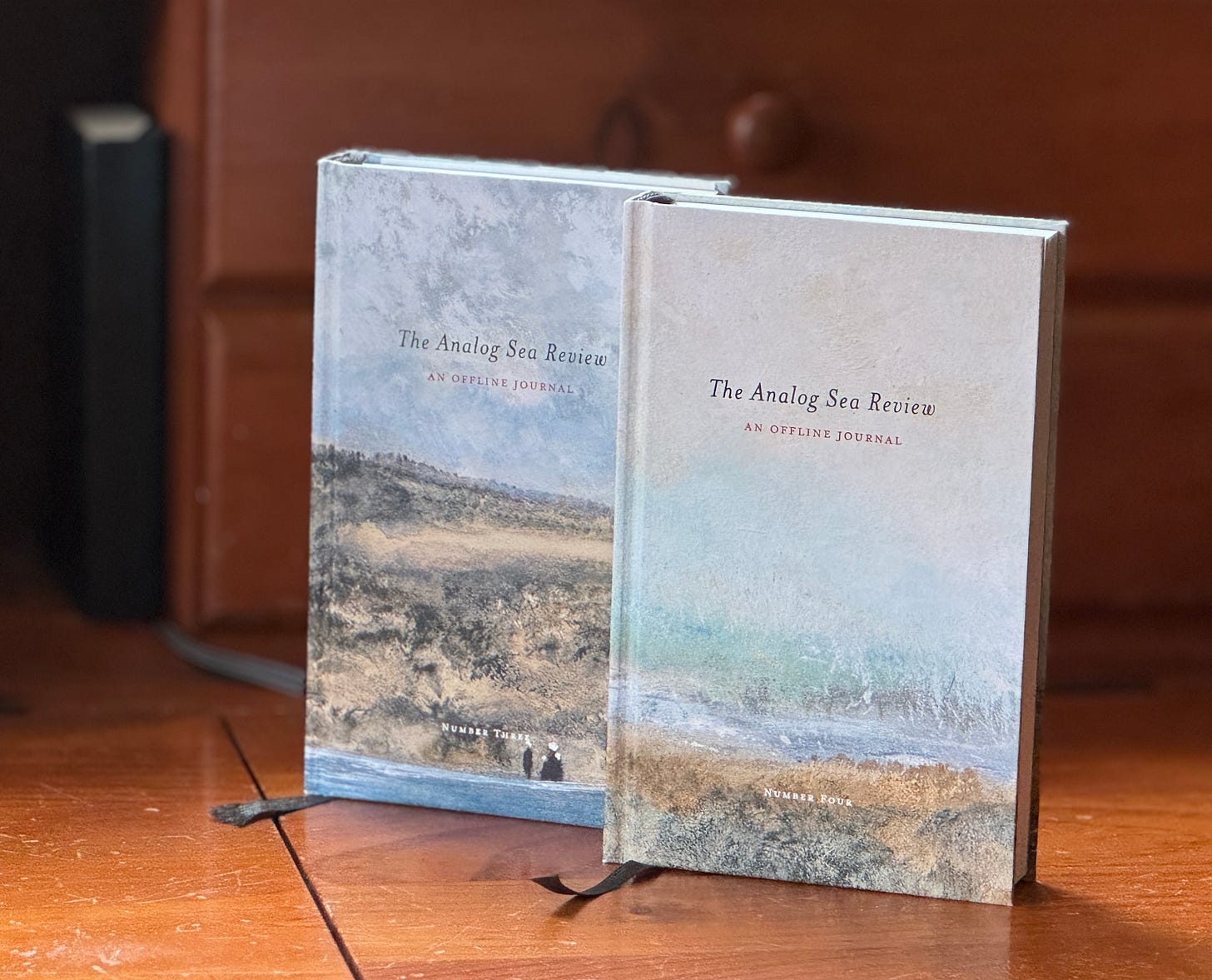

A couple of years ago, at the height of the pandemic, a friend mailed me a pocket-sized publication. It was sent by post because the publisher does not offer a way to read it—or even order a print version—online. There is no website (of course, I searched for one immediately) except for a placeholder page that simply gives you an address so you can write to them. It is called Analog Sea, and after sitting a while with this thoughtfully curated and beautifully produced collection of short writings, I was intrigued.

I am someone who embraces technology and would not be writing to you here if I didn’t. I maintain that it is a remarkable tool and I would not be enjoying the career that I have built without it. The important word here is tool… it is a tool. As long as it remains a tool and does not become a way of life, I think it can be a very good thing for humankind. We all know that the balance between technology being a tool and being a way of life is a highly sensitive scale that is leaning in favour toward being the only way to live in today’s world and into the future. The people behind Analog Sea are committed to helping it remain an amazingly helpful tool.

Included in that small booklet (Analog Sea calls them bulletins, a sampler of their current offerings) was a postcard that allows the reader to write to them and order more of their publications. There is also a list of indie booksellers that you can contact by phone or mail to order them. I decided to write a letter to Jonathon Simons, editor of Analog Sea, and a few weeks later I received one in return, including several more bulletins, a very nice clothbound journal, and a hardcover chapbook of poetry—a thank you for setting my local indie bookshop onto them as a new stockist for their books. It was a delight to receive. A few days later I sent out the bulletins to friends who I thought would enjoy them.

Analog Sea has become one of my favourite publications—a pocket-sized hardback of excellent writing by authors known and unknown to me, and a wonderful selection of visual art within its pages. The latest volume is always in my bag, a slender companion for when I find myself waiting and want to avoid reaching for my phone. What does this have to do with my goldfish-brain? I’m getting there.

Over the past couple of years, since reading a convincing essay by Jonathon Simons in Analogue Sea Review Volume III, I have made some conscious decisions on how to get back some of my ability to focus and to be in true solitude in this ever more connected digital world. The most valuable of these new habits has been the use of a commonplace book, the first of which began in the clothbound journal sent to me by the editor of Analog Sea.

A basic definition of the commonplace book is a compilation of ideas, quotes, passages and observations collected into a journal by an individual. I have named mine Woolgathering and I created a series of videos about it, the first of which you can watch on YouTube. This book, now well into my seventh volume, travels with me almost everywhere and allows me an intentional pause to think on paper and, perhaps more importantly, a place to record the writings and ideas of others that matter to me and that I wish to remember. When I first began the practice of copying text into my notebook I couldn’t remember more than a few words at a time without needing to glance back at the text I was transcribing. I’m pleased to report that over a year later I can recall complete sentences. This might not seem like a big deal, but for me it is a triumph.

I am also working on (although not as successfully) other helpful habits, like having my smartphone put away and on “do not disturb” for hours at a time instead of carrying it around everywhere I go, even to the bathroom. I cannot be the only soul who habitually takes the phone into the bathroom, can I? I am also trying to pick up an analogue notebook whenever I have the urge to hold my phone and scroll social media or YouTube, and, instead, simply write in my notebook until the urge passes. These things are still a work in progress; I have another offering for you next week about this process of being more mindfully analogue in case you might want to try some of them, too. The woolgathering book has become my touchstone, though, and my goldfish brain is slowly evolving into, I don’t know, maybe a squirrel? At least squirrels can bury nuts and recall exactly where they hid them even weeks later. Progress.

The big burning question you are surely asking: am I still burning toast? Honestly, yes, but not as often—weekly, or more, but not daily. It is also a work in progress, and I am hopeful. Very hopeful.

Kateri, I love this piece so much.

All of it. Did you happen to see the @jane ratcliffe interview with @austin kleon? The commonplace notebook is a big and gorgeous common denominator.🌱

An enjoyable and meaningful essay, Kateri! It is so, so easy to be distracted these days . Love your humor mixed with real food for thought in this one!