A quiet enters my studio in the lower level of the historic Roycroft Print Shop, just as the late morning light begins to slant through the high, small windows, when the village settles between the bustle of the early commute and the traffic of lunchtime. Sometimes it feels like the 125-year-old walls breathe with memory. The old floors creak from activity above me and now and then the hiss and churn of the boiler echoes within the walls with occasional booms and bangs that can startle me, but in between the rumblings of a century old building there is a special silence. I can hear the sound of my pencil on paper, that soft whisper of graphite meeting grain, and the swish of my brush in water can sound as present as another being in the room. There, in that small room on the Roycroft campus, I often feel I’m not working alone. Something of the old spirit lingers within my own paper, ink and intention.

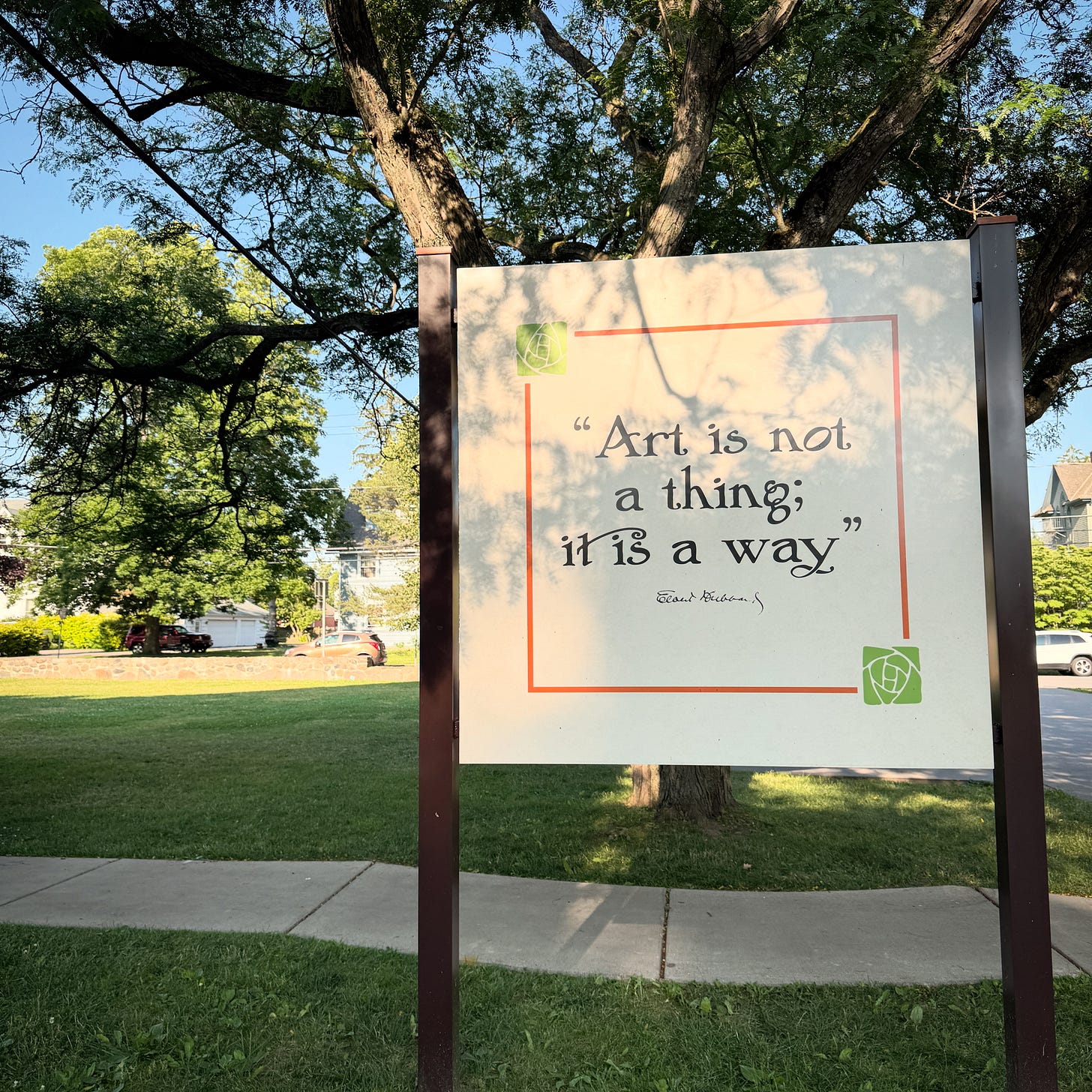

Elbert Hubbard once wrote, “Art is not a thing separate and apart; art is only the beautiful way of doing things.” These words have been widely circulated as a much simpler quote,“Art is not a thing; it is a way,” and is even printed onto a sign that hangs at the entrance to the Print Shop. Not a thing. Not a product. A way. It’s such a simple phrase, and yet I carry it like a compass in my pocket.

In 1901, Hubbard built this place where I sometimes draw and paint, and dreamed it into being as a haven for makers, thinkers, printers, poets. For him, art was in the doing, yes, but more than that, in the living. How one swept the floor, set the type, arranged the hand-made books on the gleaming clean shelf. The care with which one did their work mattered as much as the product of the work. The point wasn’t perfection. The point was presence. And that, I think, is the quiet message still woven into those print shop walls: art as a manner of living with integrity and beauty. A life made slowly, by hand, head and heart

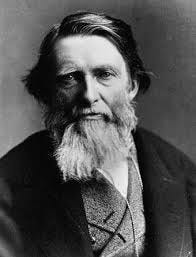

Then there is John Ruskin, a 19th-century polymath who greatly influenced and inspired Hubbard, whose Victorian prose burns with the same fire: art not as decoration, but as devotion. Ruskin believed that beauty must be rooted in truth, and that seeing clearly was a moral act. “Fine art is that in which the hand, the head, and the heart of man go together,” he wrote—a phrase Hubbard would later turn into one of his famous mottos and even carve into one of the oak doors on his campus. Long before I ever stepped into my Roycroft Print Shop studio, Ruskin was my first mentor across time and space, teaching me how to draw with tenderness and attention in the pages of his book The Elements of Drawing. It was through his voice that I first began to understand that drawing is not simply a skill, but a way of perceiving the world with humility and care. Ruskin as a philosopher and teacher also calls us back to the natural world—to the curve of a leaf, the texture of a stone, the ephemeral shape of a cloud, and to the honest labour of a maker’s hands. His was not a theory of art, but a theology of care and intention.

Years later, in another place and another time, another man would echo this truth, but through a different lens. Frederick Franck (1909–2006), artist, mystic, dental surgeon, and spiritual seeker, wrote and illustrated his book Art As a Way as a kind of lantern for the soul. He believed that in a world dulled by speed and consumption, art could be a way back to presence, a form of resistance. His drawings, spare, reverent, trembling with life, are maps of rapt attention, not meant to impress but to witness. For Franck, to draw was not to render but to truly see. “I have learned that what I have not drawn I have never really seen,” he wrote. In this way, drawing became his prayer, his meditation, his protest, his way of being in the world, and his devotion. It was not separate from his spiritual practice; it was the practice. He taught others not how to make art, but how to awaken, to slow down enough to fall in love with the curve of a leaf, the silence of a stone, the soul of a passerby, or even in a portrait of a person who lived long ago. He called this kind of seeing “the only kind of seeing that sanctifies the world.” His presence reminds me that to draw is not to escape life, it is to enter it more fully, with reverence and humility. Through him, I learned that drawing can be a vow to stay open, to stay awake, to meet the world not with judgment, but with wonder.

I don’t stand directly beside these men in my own philosophies, but I walk among their echoes. I hold their thoughts close when I pick up a pencil, when I mix paint with water, when I teach others how to see by drawing, and I hold them close even as I write these words. Each of them reminds me, in his own way, that art is not separate from life. It is how we show up to it. How we begin to love what we have seen more closely, far more than just a surface glance. How we choose to walk through the world—with attention, with grace, with something like reverence.

There is something else I bring to this lineage, something these men, for all of their brilliance, could not quite speak to: a feminine wisdom that doesn’t separate soul from soil, that doesn’t seek to transcend the world, but to kneel closer to it. A way of being that doesn’t shout to be heard, but listens and explores its way forward. One that recognises presence in all things—the hush of trees, the quiet breath of stones, the invisible thread between the seen and unseen. For me, art has never been about mastery or even about product. It has been about intimacy. It has been about learning to be with—with a line, with a leaf, with a sorrow I cannot name. It is how I tend to the ache of living, and to the joy. How I stay open. How I bear witness to both the light and the brokenness. And often, how I mend.

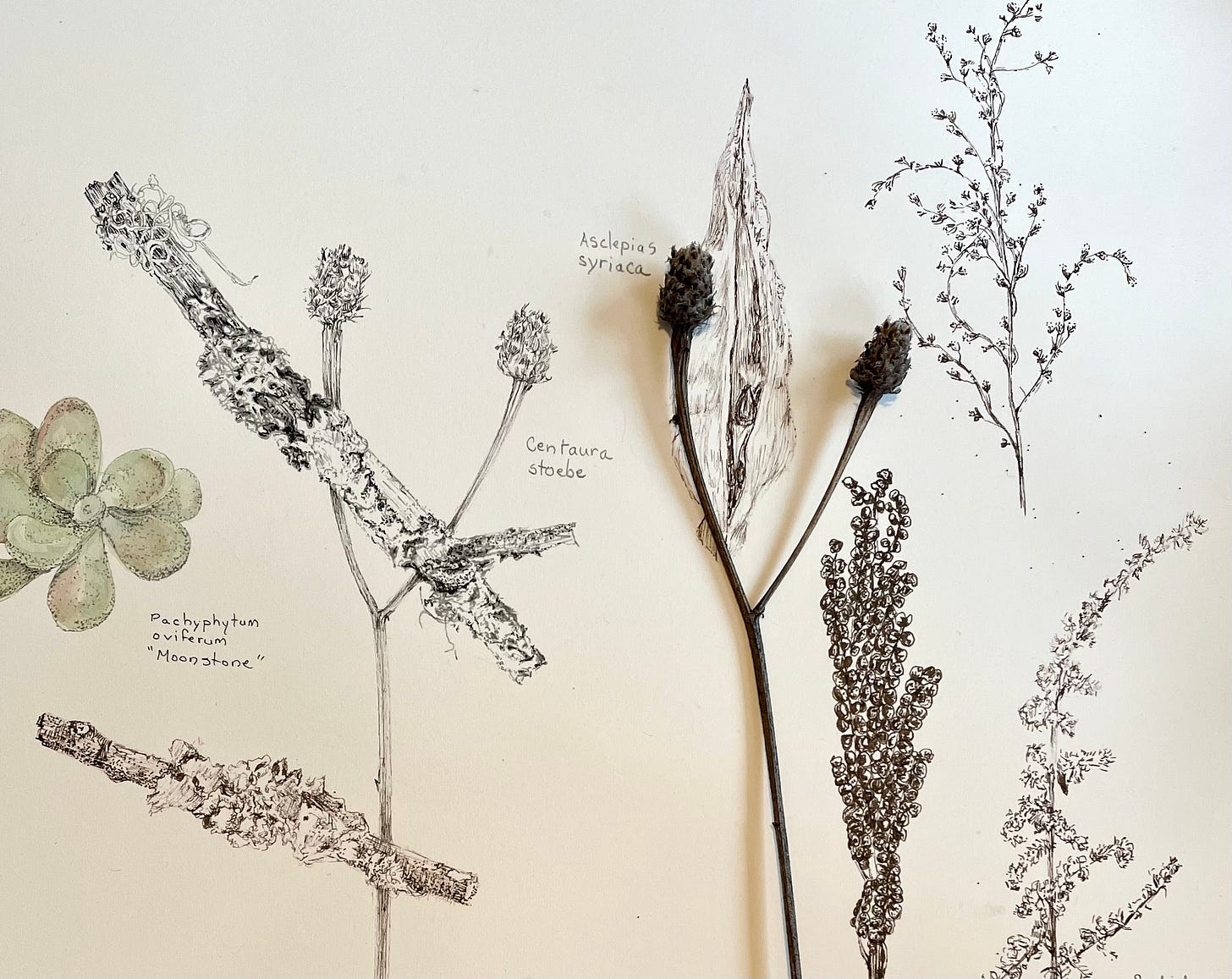

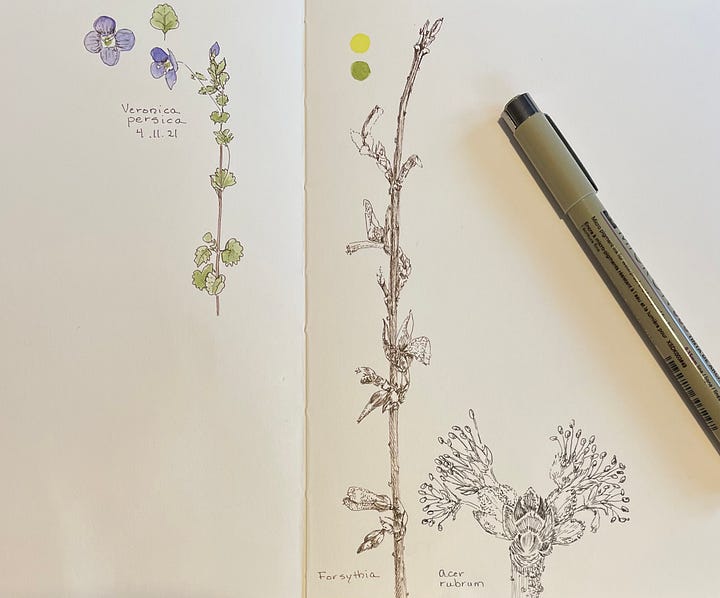

When I have sat at my desk in the old Roycroft print shop, or more often at my kitchen table at home, pencil hovering over the curve of a pear leaf or the shimmer of a bird’s wing, I feel myself entering a kind of quiet agreement with the world. I won’t try to dominate you or change you, I say in my heart, I’ll simply try to see you, to reverently document you onto this paper, and in seeing, I can remember again what it is to belong to the greater tapestry of all things.

Art, for me, is not a pursuit. It’s a return to what is real, to my breath that mixes and mingles with the breath of all other living things, to what truly matters. It is not the performance of beauty, but the practice of devotion, and it is not mine alone. There is art in the way a friend listens, hand to her heart, when someone is grieving. There is art in the way a grandmother gently brushes and then braids a granddaughter’s hair. In how someone might set the table with care even when they’re eating alone. This too is a kind of making. A kind of seeing. A way.

We don’t always need to create something “great.” Sometimes we are the artwork. Sometimes the tenderness we carry into the world is the most lasting thing we’ll leave behind. Sometimes, when the day is still and I’m alone at my desk, I watch the dust catch the light, and it feels like a kind of benediction. My pencil moves across the page, not quickly, not perfectly, but with presence. This is the work. This is the way.

Elbert Hubbard teaches me that art lives in how we live. Ruskin reminds me that beauty and truth walk hand in hand. Frederick Franck shows me that drawing is a practice of seeing with the heart. Through them, alongside them, I’ve found my own way. A quieter, more intimate one. A deeply feminine one, rooted not in achievement, but in attention. Not in mastery, but in relationship. I hope it is woven through everything I create and every lesson that I teach.

And so, if you find yourself wondering whether you are making art “enough,” or well enough, or whether it matters at all—I want to say: you are and it does. If you are living with tenderness, if you are seeing with care, if you are showing up to the moment with even a flicker of wonder, you are already on the path.

Art is not just a thing we do, it is the way we love the world. The way we carry beauty like a candle in our hand. The way we can keep showing up, even when no one is watching. Even if no one ever sees what we do. Even when it would be easier to close our eyes.

So take heart. Sweep the floor. Braid the hair. Make the tea. Draw the leaf. Write the sentence. Sit in the stillness and feel the weight of your own aliveness. It is more than enough.

Because this, too, is art.

Because this, too, is a way.

Wouldn’t that be the best epithet: “She saw.”

One of your best ever!!!!

I restacked but computer klutz that I am, didn’t know how to link your summer retreat. Please add the link if you see the restack. More people need to know you🩵🎨💚